Corn into Cornmeal at Abbott’s Mill

- Steve Childers

- Sep 29, 2023

- 5 min read

Before I explain the corn milling processes at Abbott’s Mill, I should briefly explain what the “Oliver Evans System” is. Delaware native Oliver Evans (1755-1819) lived in Newport, which is about halfway between Newark and Wilmington. In the late 1700s there was not much innovation, people tended to do things the same way it had always been done, and this included the milling process. Corn or grains were moved about the mill by hand, which sometimes meant lugging heavy bags of grain up two flights of stairs. No one had yet thought of a way to make it much easier.

In 1785 Oliver Evans and his two brothers had just finished building a grist mill on Red Clay Creek and over the next 5 years Oliver experimented with ideas he had to reduce their reliance on manual labor. His first idea was using the bucket elevator to move grain vertically.

He didn’t invent the bucket elevator, but no one else had thought to use it to move grain in a mill. Chutes had long been used to direct grain products down from higher levels and he continued to use them in their mill. He set the system up so the process was largely automatic and the only time the material needed to be handled was to dump the bags of corn or grain in a hopper at the beginning, and to change the bags of flour or cornmeal as they filled at the end. Not only did this save a great amount of time and labor, but the end product came out much cleaner.

Abbott’s Mill has two millstones that had originally been setup so that one of them was for corn and the other was for grains (wheat, barley, buckwheat, etc.).

When the roller mills were installed in the late 1800s, the older process was changed slightly so that both stones could be used for corn and all the flour production was done on the roller mills. This was 20-25 years before Ainsworth bought the mill in 1919.

At Ainsworth Abbott’s mill, when farmers brought their corn to be ground, it would’ve been in large grain bags that were unloaded onto the loading dock in front of the mill.

The corn was brought in the door on a hand truck and was weighed. If it was still on the cob it was sent through the Corn Sheller and it then fell down to a bin in the basement. If the farmer had enough children to operate a corn sheller, the corn would already be shelled and would get dumped through a grate in the floor that led directly to the same bin in the basement. The customer would then get a more favorable toll rate. From the bin the corn went to the first elevator, which carried it all the way up to the attic. There it dropped through the corn cleaner and on into one of seven large storage bins, to be ground into cornmeal later.

The corn cleaner is simply a chute with an interchangeable screen in the bottom. Corn passed over the screen and dirt and seeds fell through and down a 4-inch pipe, back to a bag in the weighing area. When the customer’s corn had all been cleaned and stored away, Mr. Abbott would weigh the dirt and seeds that had accumulated and would deduct that amount from the total that had been brought in. Millers had a saying; “We don’t pay for dirt,” and this is what they meant.

The customer would get a receipt for whatever the total was, minus a percentage for the miller. At most mills money seldom changed hands, but the miller would keep a percentage of the grain, called “the miller’s toll.” This percentage was set by law and depended on what was being ground (corn, wheat, buckwheat, etc.) When his toll it had accumulated, Mr. Abbott would grind it and would sell the cornmeal in the rural stores from Georgetown to Dover. His only employee was a man that made these deliveries.

Back to the process, if Mr. Abbott wasn’t too busy, he would probably grind that corn for the customer right then and send him on his way with his cornmeal. Or, he might promise to have it ready for pick up at a later date. Either way, he would open a sluice gate just across the road to allow the turbine well to fill with water. The well holds about half as much water as a home in-ground swimming pool might. Ainsworth would then turn the wheel that opens the vanes on the turbine so the water can flow in and start spinning the turbine blades. This in-turn starts the millstone spinning.

Insert Picture of corn chute gate

Mr. Abbott could now open the gate in the chute for whichever storage bin the customers corn was in. With six bins for customer’s corn (and one for his toll), I have no idea how he kept track of who’s corn was in what bin, but he must have had a notebook or something.

The corn would flow down the chute and into the small hopper (1) above the grinding stones. It would then flow on through the shoe (2) at a rate controlled by the crook string (3), the shoe handle (4) and the damsel (5). The corn then flows slowly into a hole, called the eye (6), in the runner stone. There are two millstones, of course. The one that spins, on top, is the runner stone (7) and the one fixed to the floor underneath is the bed stone (8). The distance between the stones can be controlled to regulate how fine or how course the cornmeal is when it comes out.

Insert Picture of Millstone Hopper

As soon as cornmeal began to flow out of the stones, Mr. Abbott would reach down and take out a hand-full, which he would rub between his thumb and forefinger to see if it felt right. He might even give some to the customer to get his opinion. If necessary, he could then make a slight adjustment to the runner stone.

From the millstones the cornmeal fell down a short chute and was picked up by the second elevator. (Mills with the Oliver Evans system nearly always had two elevators for each set of millstones, one to carry the corn or grain to storage above the millstones, and a second to carry off the cornmeal or flour.) The elevator carried the meal up to the attic where it fell down another chute to a sifter on the second floor. What didn’t go through the sifter was usually returned to the customer as animal feed. The cornmeal fell down one chute to a small hopper on the ground floor, and the feed went down another.

Both chutes were designed to hold a bag that would slowly fill with cornmeal. The gate with a handle. above the bag, was to shut off the flow when a bag was full so an empty bag could be attached.

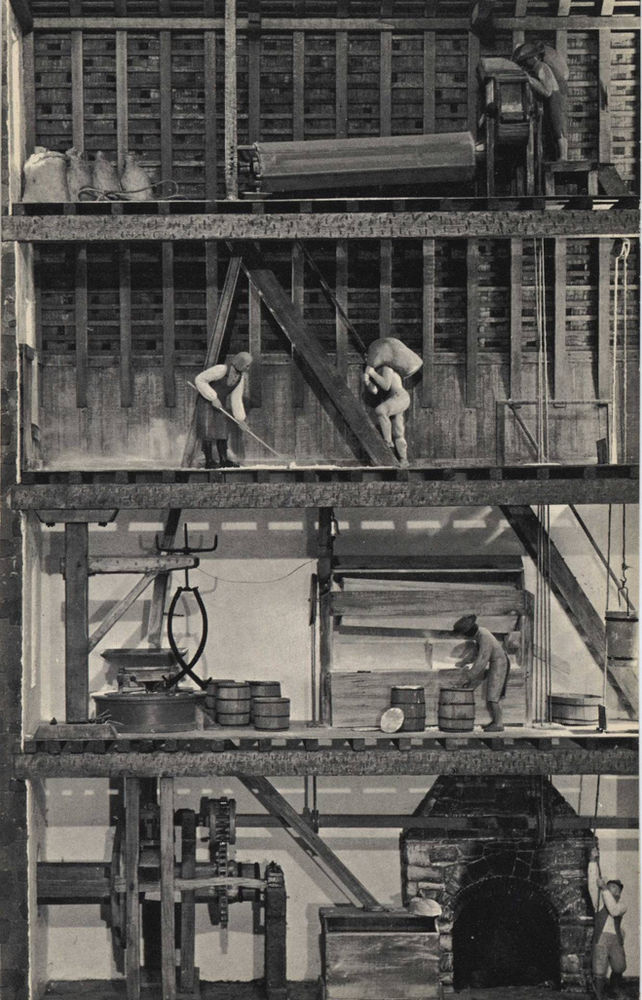

When you are able to tour Abbott's Mill, we have a nice seven foot tall working model of the entire corn operation. However, right now the mill is closed to tours for the time being due to termite damage. The goal is to have it open again in March of next year. Fingers🤞 crossed.

Next week we'll look at the Flour Making Procedure at Abbott's Mill. Buckle up, it could be a bumpy ride.

Comments